WHAT HAPPENED AT MY LAI? THE BUCOLIC SETTING OF PALM TREES, VERDANT SHADES OF GREEN, THATCHED HOUSES, AND SUN-SPLASHED PATHS BELIE A TERRIBLE EVIL COMMITTED BY AMERICAN SOLDIERS IN CHARLIE COMPANY, 11TH BRIGADE, 23RD INFANTRY(AMERICAL) DIVISION.

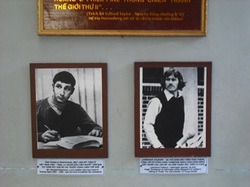

Mural of My Lai and Son My area is on display in a memorial museum of photos, artifacts, and a list of the 504 victims.

Mural of Son My area in a memorial museum.

Note proximity of the ocean shore to the left. My Lai is one of the small hamlets in the spread-out village of Son My, the name by which the Vietnamese remember the tragic outcome of an American sweep through the area.

The infantry grunts would have done better to go swimming at the nearby beach than to make March 16, 1968 a date that marks an American atrocity of horrific proportions committed against Vietnamese civilians. Visitors to the Son My museum in this remote coastal area are shocked at what they see, although few Americans make the trip.

It is little wonder that U.S. soldiers, no matter what they had been led to believe about their mission in Vietnam, were hated by the rural population who just wanted to grow rice, worship in their household Buddhist shrines, and raise a family. An ancient Vietnamese saying, "The emperor's rule ends at the village gates," was still apropos.

Sometime after the tragedy, Americans began noticing NVA captives had a patch on their uniforms with something about "Son My." They found out it was "Remember Son My," which most GI's knew nothing about until well into 1969.

The infantry grunts would have done better to go swimming at the nearby beach than to make March 16, 1968 a date that marks an American atrocity of horrific proportions committed against Vietnamese civilians. Visitors to the Son My museum in this remote coastal area are shocked at what they see, although few Americans make the trip.

It is little wonder that U.S. soldiers, no matter what they had been led to believe about their mission in Vietnam, were hated by the rural population who just wanted to grow rice, worship in their household Buddhist shrines, and raise a family. An ancient Vietnamese saying, "The emperor's rule ends at the village gates," was still apropos.

Sometime after the tragedy, Americans began noticing NVA captives had a patch on their uniforms with something about "Son My." They found out it was "Remember Son My," which most GI's knew nothing about until well into 1969.

This is sacred ground to the Vietnamese. There are mass graves and the ambiance is akin to what Americans feel when they visit Malmedy, or Czechs at Lidice, or Native Americans at Wounded Knee.

Son My Memorial site. Museum on right. Sculpture at end of walkway.

Son My is in Quang Ngai province. The nearest airport seems to be Quy Nhon from where one may take a bus or taxi 90 miles north to Son My. Quang Ngai Province lies about half way up the coast of southern Vietnam and does not contain large urban areas like Nha Trang, Quy Nhon, Hue, and Danang. Consequently, it was an area that supported the National Liberation Front with taxes and food. This atrocity imprinted on the Vietnamese that Americans would kill civilians making a mockery of being there to help them. It strengthened the Vietnamese peoples' resolve to throw out the foreign devils. One wonders how the GIs could have been so cold blooded. A bigger question is how could smart US leaders have considered the totality of Vietnam a threat to America. This was the heart of darkness.

This reporter has spoken to various groups back in the United States, often including Vietnam veterans. Usually, one of them will get up and deliver a soliloquy about how the Americans had been booby trapped for several weeks causing some KIAs, and the people of Quang Ngai hated them and conspired against them, etc. etc. I let them talk. When they are done, I say, "Oh, you mean the big bad enemy made them do it? If you can't hold on to standards of morality in a war zone, then maybe you're in the wrong war."

This reporter has spoken to various groups back in the United States, often including Vietnam veterans. Usually, one of them will get up and deliver a soliloquy about how the Americans had been booby trapped for several weeks causing some KIAs, and the people of Quang Ngai hated them and conspired against them, etc. etc. I let them talk. When they are done, I say, "Oh, you mean the big bad enemy made them do it? If you can't hold on to standards of morality in a war zone, then maybe you're in the wrong war."